The 'Liber Farnese': Between Dynastic Heraldry and Botany at the Venerable English College in Rome

Four hundred years ago, on 21 February 1626, Cardinal Odoardo Farnese died in Parma. A patron of several English Colleges in Europe, including the Venerable English College in Rome, he belonged to the formidable Farnese dynasty that produced Pope Paul III and played a decisive role in shaping the political and artistic landscape of early modern Italy.

Portrait of Cardinal Odoardo Farnese by Domenichino, c.1602-1603, Palazzo Farnese. ©Andrea Ciaroni and licensed under Creative Commons:

Born in Rome on 8 December 1573, Odoardo was the third child of Alessandro Farnese, duke of Parma and Piacenza, and Maria of Portugal, a cousin of Philip II of Spain. As a dynastic spare, after Margherita (1567) and Ranuccio (1569) his path was defined early. An ecclesiastical career offered a path that combined dynastic security with political ambition: it preserved family interests while consolidating Farnese influence in Rome. Odoardo’s formation began in Rome in 1580 under the watchful eye of his great-uncle, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, and the noted humanist and Farnese librarian Fulvio Orsini.

Seeking to succeed his uncle’s vast network of ecclesiastic benefices, Odoardo’s early advancement within the Church was constrained by Pope Sixtus V, whose hostility to the Farnese family curtailed Odoardo’s ambitions and restricted his clerical progress. His circumstances, however, soon shifted in his favour. In 1591, Pope Gregory XIV elevated the eighteen-year-old to the cardinalate, disregarding his disqualifying youth and concerns about kinship. From then on, Odoardo embodied the hybrid identity typical of great Roman cardinals: prince and prelate, dynast and churchman.

At the turn of the century, his career briefly intersected with European monarchy. On 19 February 1600, Pope Clement VIII appointed the twenty-six-year-old Odoardo as Protector of England. This role, tied to Farnese–Aldobrandini alliances between his brother Ranuccio and his wife (also the pope’s niece) Margherita Aldobrandini, fed dynastic hopes that the Farnese might lay claim to the English throne upon the death of Elizabeth I.

The Farnese brothers counted themselves among the many contenders for the English throne, grounding their legitimacy in descent from the Lancastrian line through their mother, Maria of Portugal. Notably, her naming of her second son, Odoardo, was a calculated dynastic allusion to her forebear, Edward III.

The scheme formed part of a broader vision of Catholic renewal in England, centred on a projected Farnese union with the Scottish Catholic claimant Arabella Stuart. With Ranuccio Farnese married to Margherita Aldobrandini, Odoardo’s cardinalate could, in theory, have been transformed into a royal vocation in service of the Church. Yet the plan depended on French and Spanish backing, and neither power proved supportive: Spain promoted its own candidate, Isabella Clara Eugenia, while France judged the proposal impractical and diplomatically risky in light of James VI of Scotland’s likely succession. Papal diplomacy soon withdrew its support. Odoardo nevertheless sustained his ambitions, drawing authority from his title of Protector of England and from his patronage of the English colleges in Rome, Valladolid, and Douai. Through these institutions, and in alliance with the Jesuits, particularly Robert Persons, he sought influence within English Catholic affairs. The accession of James VI (and I) in 1603, however, effectively extinguished Farnese hopes. Odoardo ultimately remained within the Church and was ordained priest in 1621.

A churchman by dynastic necessity rather than personal vocation, Odoardo remained a princely clergyman through his final years, holding onto his secular habits until the end.

He died in Parma on 21 February 1626 at the age of fifty-three, and was buried in the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome, whose construction had been financed by his great-uncle Cardinal Alessandro Farnese.

It is in the context of this princely cardinal, at once ambitious, erudite, and deeply embedded in the arts, that the Venerable English College in Rome preserves a remarkable manuscript connected to his death: the Liber Farnese — a remarkable illustrated manuscript recording the ephemeral ‘decorations’ erected for Odoardo’s funeral rites.

The Liber Farnese

Baroque representations of magnificence were not confined to triumphal festivities; death, too, offered elaborate opportunities for carefully orchestrated displays of splendour. Funerary ritual provided an occasion for spectacle equal in grandeur to triumphal entries or dynastic weddings. Temporary or “ephemeral” decorations transformed public spaces, including churches, into evocative theatres of memory. These structures, often elaborately designed and painstakingly manufactured yet lasting only short spans of time, articulated enduring claims about lineage, virtuousness, devotion, and authority.

The Liber Farnese, a manuscript of 22 leaves (measuring 20 × 27 cm), records precisely such ephemeral interventions staged in the original chapel of the Venerable English College in Rome. The title alone ‘Ristretto Della solennità funerale celebrata nella chiesa Del Collegio Inglese Per l’esequie fatte nella morte Dell’ Ill’[ustrissi]mo Cardinal Farnese Protettore del medesimo Colleggio’ makes clear its commemorative intent.

Thus, following the title page and the Farnese crest, the document presents carefully executed illustrations of the temporary funerary apparatus. The odd pagination, blank double pages, and occasional trimming of certain details of the painted images suggest that the drawings were originally prepared as loose folios and only later cut and bound together, perhaps as a record or draft for a projected publication. It is also important to note that each image is accompanied by brief notes, written in Italian on the edges of the pages, specifying the precise location of the physical device within the church. Written in the past tense, these annotations seem to confirm that the manuscript was compiled after the ceremonies, transforming ephemeral display into durable documentation.

The first drawing, depicting the catafalque, is particularly telling as it foregrounds the Farnese lily from the onset. Adorned with an array of Farnese coats of arms bearing the House’s dynastic lily, the construction is shown surmounted by a sculptural, prop-like lily placed at the apex of the structure. Although the heraldic flower is only partially visible, with the sheet having been trimmed to accommodate the document’s format, this intervention not only exposes the material conditions of the manuscript’s production but immediately draws attention to the shrewd semiotics of the funerary decorative programme. By crowning the catafalque, the lily would have operated as the ceremony’s visual pivot, anchoring and sharpening the funerary rites into a single emblem, which, as we learn from the ensuing pages of the manuscript, entered into dialogue with the other ephemeral installations forged around this heraldic flower.

What follows the drawing of the catafalque are illustrated panels praising the deceased cardinal, adorned not merely with heraldic lilies but with vegetal forms of the lily, whose stems and leaves resemble living plants. It is here that the manuscript’s ingenuity becomes fully apparent, as it moves beyond a merely commemorative function to stage a complex exercise in allegorical imagination, merging the spiritual world of symbolism with the terrestrial realm of natural history.

The catafalque (folio 3r)

The Lily

The fleur-de-lis, now most commonly associated with the French monarchy, long predates heraldry. As Michel Pastoureau observed, the stylised lily appears across ancient civilisations, spanning Mesopotamian cylinders, Egyptian bas-reliefs, Mycenaean ceramics, and Sassanid textiles as well as Gallic and Mamluk coins, Indonesian clothing, Japanese emblems, or Dogon totems. By the later Middle Ages, it had become a potent symbol of purity and royal legitimacy. Notably, as an emblem of purity, the lily was adopted by the Roman Catholic Church and became associated with the sanctity of the Virgin Mary.

Echoing several other European dynasties and important families, the Farnese adopted the lily as part of their heraldic language, visually aligning themselves with ancient and sacred authority. In a Europe where aristocratic ascent required more than wealth or military success, imagery mattered. Heraldic devices supplied historical depth and divine resonance. The lily, with its layered associations, proved particularly apt for a family consolidating its status among Europe’s ruling houses.

In the Liber Farnese, this symbol is reimagined with striking inventiveness. Six panels, which adorned the Church of the Venerable English College in Rome, trace the cardinal’s life through the growth of a lily that merges botanical realism with the language of heraldry. The iconographic cycle thus unfolds as a carefully constructed hybrid of vegetal form and heraldic sign, in which a naturalistic botanical plant culminates in a bloom shaped as the stylised fleur-de-lis. Adopting the format of Renaissance emblems, each image pairs a visual scene with an explanatory motto and brief text.

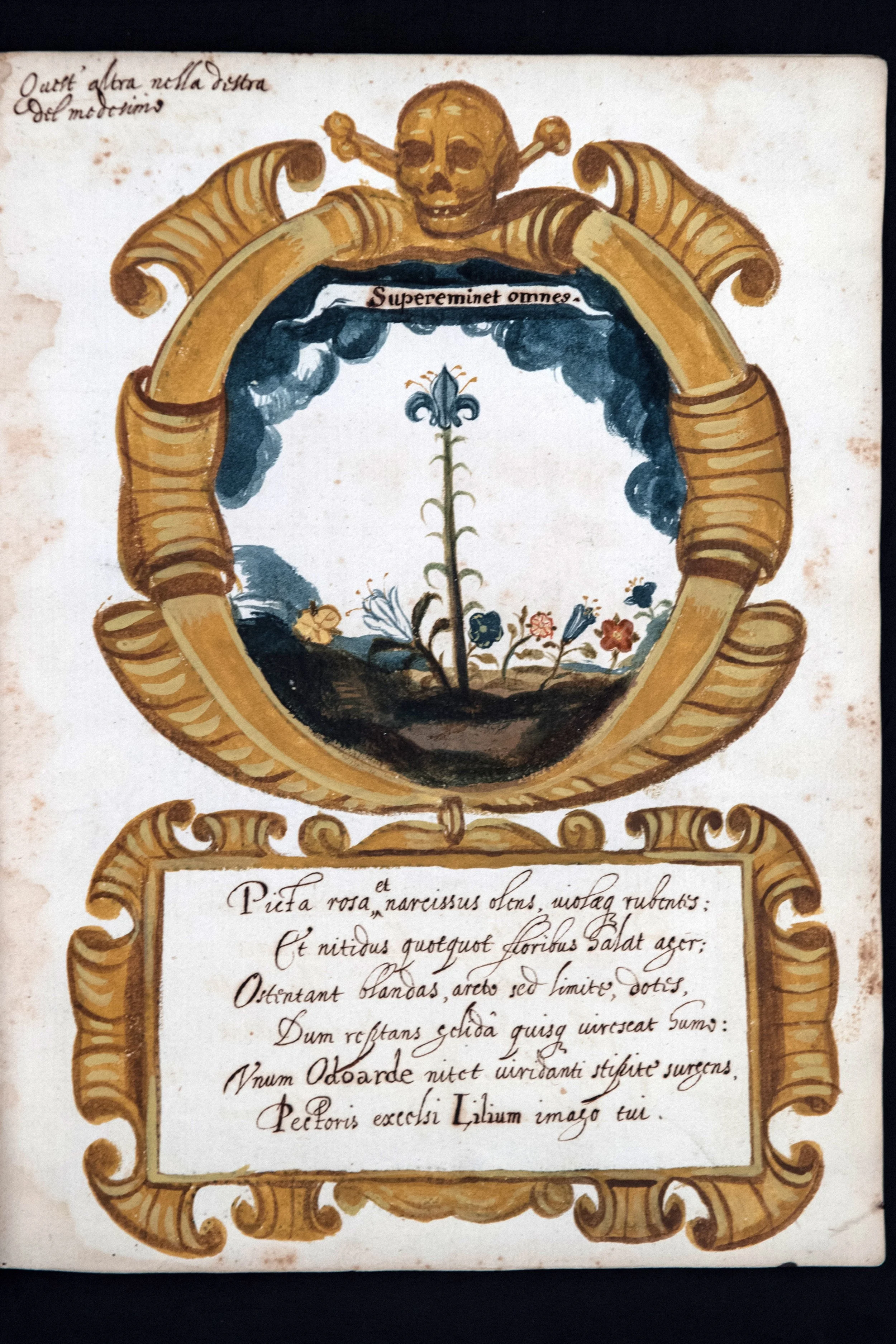

Panel 2 (folio 8r)

The first panel presents the lily rising vigorously from the earth, surpassing clouds and reaching toward celestial heights. The metaphor is direct yet effective at evoking Odoardo’s ascent within Church and court. In the second panel, the flower no longer merely ascends but surpasses all others, (Supereminet omnes), its elevation now signalling pre-eminence. Towering over lesser flowers, this is a transparent allusion to rivals left earthbound. The third panel introduces resistance: terrestrial weeds enclose the lily’s stem, yet the noble flower withstands them, conveying an allegorical rendering of the political rivalries within the fraught world of Papal Rome. The fourth panel shifts from external struggle to interior quality. Here the lily is praised as beautiful from within (Pulchra ab internis), commending its innate moral and spiritual values. The fifth panel, expands this logic outwards, framing the lily cosmologically as a celestial phenomenon. Here it is no longer merely a flower among others, as it becomes a luminous presence inscribed in the heavens, the object of hyperbolic dynastic exaltation. The final, sixth panel tempers this trajectory of elevation. Beneath the motto, Quo altius eo demissius (the higher, the lower), the image presents a bent, withering lily. Heights entails humility; elevation anticipates decline. Thus, the botanical life of the flower mirrors the arc of man: growth, flourishing, and eventual submission to wilting and mortality. The cycle naturalises princely ambition, yet simultaneously disciplines it, tempering ascent with Christian humility and resignation.

The manuscript concludes with laudatory poems in eight languages: Greek, Tuscan, English, Roman, French, Latin, Welsh, and Irish, which underscore both the international character of the Venerable English College and Odoardo’s role as its protector.

Cardinal Odoardo’s Artistic Patronage

The funerary imagery of the lily did not emerge ex nihilo. Odoardo’s long-standing engagement with this motif can be traced to his artistic patronage in Rome. In 1593 he invited the Carracci brothers to the city, an initiative that profoundly shaped the Roman art scene. Their work in the Palazzo Farnese culminated in the celebrated Galleria Farnese ceiling, painted by Annibale Carracci between 1597 and 1601.

Significantly, the botanical lily appears in preparatory designs linked to this milieu, conceived in collaboration with his tutor, the humanist Fulvio Orsini. In one instance, the lily, tinged purple perhaps in reference to cardinalitial dignity, bears a Greek maxim: “I rise towards God.”

The lily extended even into the sartorial sphere. A surviving chasuble associated with Cardinal Odoardo bears an embroidered rendition of both the heraldic crest and the botanical emblem. Liturgical vestments thus became vehicles of dynastic semiotics, readable, at least to the initiated, as statements of lineage and aspiration.

The Liber Farnese therefore participated in a longer visual and symbolic tradition cultivated by the cardinal himself. Its emblematic panels did not merely commemorate; they reactivated a vocabulary already embedded in Farnese patronage.

Ephemerality and Memory

Elaborate catafalques and their accompanying ceremonial apparatus, termed ‘castles of sorrow’ or castrum doloris, transformed churches into immersive spaces of dynastic theatre. By merging heraldry, allegory and magnificence, they asserted continuity even as they acknowledged loss. The Liber Farnese captures this paradox. It records the ephemeral installations designed to vanish, yet it preserves them with meticulous care. Its hybrid lilies, simultaneously botanical and heraldic, embody the fusion of nature, lineage, and theology that underpinned Farnese self-fashioning.

While many aspects of the manuscript remain to be studied in depth, it already offers rare insight into the practical and imaginative dimensions of an early Baroque funeral. It reveals how ecclesiastical ritual, ephemeral art, and dynastic symbolism converged within the space of the Venerable English College in Rome.

In doing so, it invites us to reconsider funerary spectacle not as ancillary to political life but as one of its most eloquent stages—where theology, heraldry, and artistic invention met in a final act of princely display.

In Cardinal Odoardo Farnese’s case, that final act did not merely commemorate his death but crystallised the dynastic, spiritual, and political ambitions that had shaped his life.

Requiescat in pace

A broader article on the Liber Farnese and its hybrid iconography, merging heraldry and botany, is currently in preparation for the Papers of the British School at Rome.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Dr Jane Eade, Director of Heritage Collections for the Venerable English College, Dr Renaud Milazzo, the College's Library and Archive Manager, Professor Maurice Whitehead, and the British School at Rome for their essential roles in facilitating my access to this unique and remarkable document.